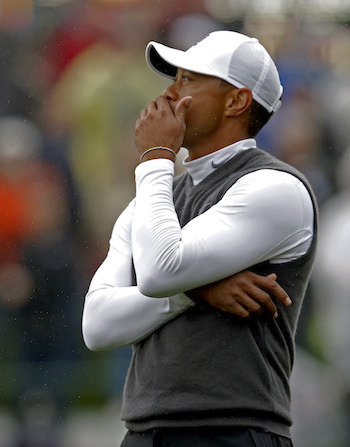

His obits are already appearing and, very pertinently, to the majority, the reports of his demise do not seem in any way exaggerated. Tiger Woods is finished. Only the last freakish acts remain; the pitiful postscript, the wildly inappropriate finale. Think Elvis in Vegas, Ali in the Bahamas except it does not have to end like this. Of course, we can dismiss his chances of a fifth Green Jacket in the Masters next month, no matter if next week he does announce that he will play at Augusta.

Yet just because the condition of his mind, body, swing and reputation appear so bleak, and just because a number of the younger professionals are presenting their major candidatures so strongly, it does not necessarily follow that Woods has no future at the top of the game. To believe it does is to get sucked into the “fallen icon” narrative which is far too simple and ignores not only the details of his own professional history but, just as pertinently, the history of his own profession.

Let us start with the injury and his form before it; two facts which are conveniently overlooked in the apparent rush to write him off.

Think back to 2013. That season Woods won five times, more than anyone else. No, the titles were not of the major variety, but the fields were of at least a comparable quality. At the Players Championship – aka “the fifth major” – and the two World Golf Championships, the Cadillac and the Bridgestone, Woods destroyed the best by a collective 11 shots, reclaimed world No. 1 and was to win the player-of-the-year awards easily. This was not last decade; this was not even two years ago. And it happened to be when he was last fit.

In truth, the memories of that two-shot triumph at Firestone, that seven-shot stroll at Doral, should still be fresh. That they are not is because of a herniated disc and the daft expectancies of Woods thereafter.

When it was announced in early 2014 that Woods required a microdiscectomy – a procedure which removes a piece of spine – Graham DeLaet told us that it would take a least a year to recover. The Canadian was well placed to make his estimation; he had gone through the same surgery two years before. Yet, in defying the medics and their conventions, Woods returned in less than four months. It was too early; as DeLaet said it would be. Woods was forced to shut down again, essentially for the rest of the season; as DeLaet said he would have to. Now Woods insists that he is at last fully recovered. No shock there. Next week will be the 12-month anniversary of the surgery. A year; as DeLaet said it would be.

But the naysayers scream that Woods will never be the same, will never get over it. Why? DeLaet did. In fact, when he eventually resumed his career, DeLaet had his best year, rising to the brink of the world’s top 30. There is no evidence to believe that Woods is finished because of that back complaint. Anything but.

However, at the start of 2015, we see him shooting a career-worst 82, pulling out with muscular pain and taking another indefinite leave of absence and we assume it is primarily because of his “condition”. But this break is because he has the chipping yips. Woods is not competing because he cannot compete. But again, it does not provide incontrovertible justification to sound the Last Post.

Granted, the chipping yips have the potential to ruin a career, to destroy a competitive psyche. They are harder to address than the putting yips and Woods’s former coach, Hank Haney, is adamant that, to quote Tommy Armour: “Once you’ve had ‘em, you’ve got ‘em.” But even Haney agrees that it does not have to be terminal and that, while they will strike from time to time, tournaments and, yes, majors can still be won.

If and when he finds respite from the yips and if and when the latest swing change beds in, Woods will still be capable in the majors. True, Rory McIlroy has raised the bar and the precocious likes of Jordan Spieth and Patrick Reed do appear major-ready. But to assume that this new generation will monopolize is to discount the record books and discredit the sport’s huge appeal.

Because of its nature, golf, more than any other sport, allows its contestants the enduring hope of opportunity and, to feel positive, Woods would only have to look at the last 10 major winners. Only two were in their twenties, while three were in their forties. The comeback stories of Ernie Els, Darren Clarke and, to some extent, Phil Mickelson prove what is possible, as do the legends of Hogan and Jack Nicklaus and so many others whose time was supposedly done and dusted.

Woods is only 39. It is not yet over. It is just very tempting to bundle his troubles in a package, in a salutary lesson of hubris, and depict it in that manner. But let us afford Woods the respect of waiting until we take the chisel to his gravestone.

The Daily Telegraph